Tribute to a Wise and Humble Abba

It is a daring undertaking to speak about a person; much more so, if this person happens to have been a spiritual contender, one who struggled victoriously for a whole lifetime over issues concerning man and God; and particularly so, if this person became a teacher of truth and a servant of the Most High. For there is no greater majesty in this world than for mortal man to be able to invoke the descent of the Holy Spirit and He to descend always and by necessity during the celebration of the Divine Liturgy and the Mysteries of the Church.

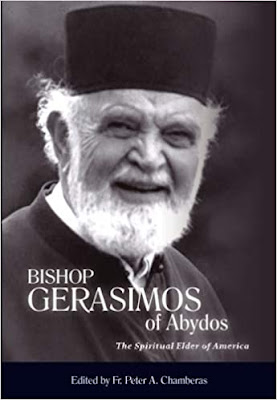

Seeker of the truth, teacher of the truth and servant of the truth was the Bishop of Abydos, Gerasimos of blessed memory. Having lived a full life, eighty-five years in all, he fell asleep in the Lord at the Deaconess Hospital of Boston after a difficult heart operation that took place on June 2, 1995. The operation was followed, unfortunately, by a series of strokes which prevented him from regaining consciousness. He gave up the spirit on June 12, 1995, the day of the Holy Spirit. His Funeral Service was chanted on the 15th. In the interim the relics of the blessed bishop lay in state in the Chapel of the Holy Cross for veneration by the faithful. Temporary interment at Forest Hills Cemetery took place on the 16th of the same month and, about six months later, the relics of the blessed bishop were returned to the campus of Hellenic College and Holy Cross for interment adjacent to his beloved chapel, where he had prayed daily, clebrated the Divine Liturgy, and ordained spiritual sons to the Holy Diaconate and the Holy Priesthood.

During his last days and hours, he was surrounded by clergymen and laymen, former students, spiritual children, and also by more relatives than he had ever had around him when he was alive in this world. He never wanted his students and spiritual children to feel that he was tied to his relatives, whom he nonetheless loved a great deal, and whom he assisted magnanimously in various ways, always discreetly.

What followed the falling asleep, at the Funeral Service and the interment of the blessed bishop, was a marvelous surprise. The cleric who never sought official recognition and great thrones, the man who did not want authority because it was an obstacle in his spiritual life, at the hour of his end had with him a huge gathering of clerics and lay people, both officials and simple believers. His Eminence the Archbishop of North and South America came quickly from New York, together with His Excellency Silas, the Metropolitan of New Jersey. Also present were the Right Reverend Bishops Iakovos of Chicago, Methodios of Boston, Alexios of Troas and Anthimos of Olympos. There were about one hundred priests from literally all regions of the American continent. The Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston, Cardinal Bernard Law, was there with his higher clergy, as were Protestant Pastors, official representatives of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and a multitude of people.

And all this for an aged bishop who had retired from his Diocese eighteen years earlier, for someone who had no authority, who served the Liturgy in the Chapel of the Holy Cross as a simple priest, and who lived as an ascetic in two rooms of student housing that he never locked. In those two rooms an utter simplicity of objects reigned. Only his books and an icon of St. Paul were objects of value. Everything else amounted to nothing at all. Whenever someone would give him a valuable gift, he would find a way to be relieved of its burden by giving it away where it might be needed.

He lived obscurely and ascetically, in the sense that he constantly attempted to remain free from worldly things, from ambitions and all forms of honors. And while he lived this way without glory and riches, everyone knew that up there, in those two always unlocked rooms, there lived a good and wise Elder, a Bishop and Professor, a humble and significant author. Above all, everyone knew that there was a Spiritual Father, who heard the troubles and problems of each person with patience and love, with deep understanding and much knowledge, with prayer and the spirit of God. Thus he had become the Abba of America, particularly for the Greek clergy, but also for the students of Hellenic College and Holy Cross School of Theology. At times of inner difficulties all could find refuge and spiritual help in the ascetic cell of Abba Gerasimos, Bishop of Abydos. This is why it is not at all strange that this person, who neither had nor wanted authority, reigned in the hearts of the people. And he cherished with satisfaction the love and the respect of so many people; this sufficed and filled him. And for this he was always grateful, to God and to men.

The marvelous, balanced and spontaneous eulogies offered by His Eminence Archbishop Iakovos, His Excellency Metropolitan Silas of New Jersey, His Grace Bishop Methodios of Boston, the Reverend Father Alkiviadis Calivas, the Reverend Father Nicholas Katinas, representative of the clergy, and all the other related expressions of love, confirmed the profound and universal esteem for the person of the blessed Bishop Gerasimos, about whom from time to time and from all directions one could hear, aloud or in whispers, officially or unofficially, the words that said it all: "He is a saint!" And it must be added that he was also unmoved by honors. It is most characteristic that after Holy Cross School of Theology unanimously bestowed upon him an honorary doctorate in 1982, Bishop Gerasimos never spoke about this honor in Greece, nor did he use the title on cards or publications. He does not even record the event in his autobiography. He did not consider it something significant.

What was the personal spiritual journey of this blessed bishop, what elements determined it, and how did he pursue his own "good struggle?" We shall attempt to briefly sketch his journey, with information that he himself left, and with additional facts that we have. (The basic elements of this sketch were delivered as a eulogy on the evening of June 15, 1995 in the Chapel of the Holy Cross at the School of Theology).

Early Family Life

He was born on October 10, 1910 in the town of Bouzi (today called Kyllini) in the province of Corinth. The poor and inaccessible town lies above the lake of Stymphalia on the slopes of Mount Tzereia at an altitude of 1300 meters. There are few fields and multitudes of sheep and goats. His father was Ioannis Papadopoulos, with the nickname Bazdinas. He was a tall and unsubdued man who lived from his teenage years (without paternal support) with his flock in the mountains or in the winter quarters. He was quick tempered, impatient and strict with all things and all persons. But he had a rare integrity and could see far into life, and he was always ready to make any sacrifice for his children - ten in number.

His mother, Athanasia, was of a different character. She was a meek and prudent person, charismatically patient and pious, industrious and dedicated to her family. She was illiterate, but in her soul she had so much love that she could love God and all those around her as well. Her fourth child, Elias, later to be named Gerasimos, received from his father a sense of honor, an unsubdued spirit and the ability to endure hardships. From his mother, in turn, he received the spirit of patience, piety, love and prudence.

The young Elias differed from all his siblings. He did not fight with them, and they, without being aware of it, treated him differently from other children. The same was true with his parents. They rarely had to discipline him. Shortly before completing elementary school his father told him: "Elias, you see that we are many; you will have to go away to make a living. I want you to become a priest. And I will help you." But young Elias was startled and, knowing the town priest to be a tall and erect man, he muttered: "But I am so short!" Then his shepherd father, who had a rare sense of humor bequeathed also to his son, explained: "Priests are not made by the yard!"

His mother's brothers, the Brilaioi, who were merchants, craftsmen and farmers in Nemea, and one a civil servant in Patras, opposed the idea of Elias becoming a priest, and his father relented which was something rare for him.

Elementary School - The Young "Pappou"

In four years Elias had completed elementary school in Bouzi. For Hellenic school he needed three more years during which he had to go back and forth by foot to Kalliani, a larger nearby town. This was more than two hours walking every day for three years. There everyone, teachers and pupils, saw Elias in a different light, without being conscious of anything in particular. It was due to his prudence which made him appear a mature young man, to his intellectual capacity to understand and, in particular, to his disposition which brought calm and peace to the students, shepherd boys inclined to running unrestrained in the mountains. During that time, his fellow students, whenever they would speak about him, would refer to him as the pappou (grandfather). "Let's ask pappou," they would say. One day a student insisted that what he had written on the blackboard was correct. And when the teacher asked why he insisted, the student retorted: "Pappou told us to write it this way!"

Grocer Boy and Clerk

At the age of thirteen Elias completed Hellenic school. It was summer and his mother sent him high up the mountain to take some food to his father at the sheepfold. There the father told Elias that he wanted to see him become a merchant and would now send him to Nemea to work wherever he could. The young boy did not object, and in 1923 Elias went to the Town of Nemea to work. He became a grocer boy at first and later worked as an apprentice to a shoemaker. In 1925 his uncle decided to send him to Patras. There he worked in various shops and, for a longer period, in a forge until 1928.

Novice at the Mega Spelaion Monastery

It was during this time in Patras that God spoke decisively. A friend of his, also a young worker, took him to an evening sermon given by the then young and fiery archimandrite Gervasios Paraskevopoulos. During this same period he read the Life of St. Alexios the Man of God. Whenever he listened to the preacher or read the book he was simply pleased. He felt something strange. He felt as if everything was already inside him and was just now being uncovered, being raised to his consciousness: love for the Church, total devotion to God. It was then that Elias received the Sacrament of Confession for the first time in his life, and this event indeed marked him decisively.

For three years he cultivated in his mind and in his heart the great issues, that is, what shall he do in his life regarding the Church and God. His own family knew nothing at all. Archimandrite Gervasios, who had surmised a great deal about the significant things happening in the soul of the adolescent Elias Papadopoulos, advised him to study at the Theological School of Arta, but the necessary funds for such an undertaking were not available to Elias.

St. Gervasios of Patras (+ June 30, 1964), canonized by the Ecumenical Patriarchate on November 16, 2023. St. Gervasios was a spiritual child of St. Nektarios and was a childhood inspiration for Bishop Gerasimos (source)

Meanwhile he heard a little and read even less about monasteries and monasticism. He constantly had the feeling that a life devoted absolutely to God was something that appealed to him. He would not say anything to anyone. Fr. Gervasios had suspected it and tried to dissuade him. He was a zealous worker and a shepherd absolutely devoted the work of preaching. That whole region was deeply indebted to him. But Elias did not delay in making his great decision to abandon worldly things, the usual joys and the usual problems.

In 1928 at the age of 18 he left everything - work and relatives who knew nothing -and arrived at the famous Monastery of Mega Spelaion He surrendered himself to monastic life without any expectations. He knew only obedience and service as a novice under the abbot and geronta of the monastery. He was drawn by the liturgical life. While he did not understand much in the Services or the Divine Liturgy, nevertheless, everything pleased him profoundly.

The months passed at the monastery and the Elder was pleased; his novice was making progress. Everything seemed good, except for an inner-most disturbance, which was beginning to grow in the soul of the novice Elias. There was a growing desire in his soul for a more austere, a higher form of spiritual life.

On the Holy Mountain - The Skete of St. Anna

For months this inner turmoil troubled his being. Before completing two years in Mega Spelaion, he had decided to go up to the peaks of Orthodoxy, the acropolis of monasticism, the Holy Mountain - Mount Athos.

With strange coincidences, which can only be explained as divine interventions, he set his destination for the Skete of St. Anna. There he served as a novice monk under the guidance of the Monk Chrysostomos Kartsonas, who lived in the kalyva - cell - dedicated to the Presentation of the Theotokos to the Temple. He stayed there only because it was the first kalyva on Mt. Athos in which he had ever entered. He considered it the will of God that he stay there.

His Elder, Fr. Chrysostomos, who treated him very well, was very meticulous with his monastic duties. But he had no special training nor was there anything extraordinary about him. On the contrary, he was of a difficult character. And from the novice Elias a lot was expected. But he did not complain. Elias tried to meet other more advanced Elders and to draw from them like a bee anything extraordinary that they had acquired through their many years of prayer and the practice of obedience. Within the skete, also under the direction of his Elder, there were others who could help Elias learn the monastic life. In another kalyva of the Skete there were two brothers who were famous iconographers and excellent monks. A little above the Elder's kalyva, in the Kalyva of the Theophilaioi, there lived another monk, a fellow countryman from Kalliani by the name of Anthimos. He became a great ascetic and a famous Spiritual Father Confessor, and with persistence acquired a great theological education by reading patristic and ecclesiastical books. Ultimately Elias was tonsured a monk receiving the name of Gerasimos.

At the Skete of St. Anna, the monk Gerasimos made speedy progress in his spiritual life. He developed the virtue of obedience and became very dear to all the Elders of the Skete. They so valued his virtue and his prudence that they all accepted - except for one - his peace-keeping intervention. His Elder, contentious as he was, had quarreled with most of the monks of St. Anna. His obedient young monk managed in three or four years to make peace among all of them.

The virtue of peacemaker would accompany him all of his life. It would be practiced as the work of a Father Confessor, who brings peace to souls that are deeply troubled. This too is one of his charismas, one of his gifts to the world. Whenever I would ask him what it was that he received from the Holy Mountain, he was disarming in his response. There he had learned to believe deeply and absolutely, to live the Tradition of the Church, as he found it and as it was being lived by all the generations of believers. This explains the form of his subsequent aspirations, his ventures into philosophy, his research and broader studies in European and American universities. They all had the conscious purpose of confirming the simple and unquestioned faith of the monks of the Holy Mountain, of demonstrating that the serious seeker in high theology and philosophy must attain the piety of a simple monk. He often said that he believed and communicated with God as his illiterate mother and as a simple Hagiorite monk. But then he would explain that he studied, taught, and celebrated the Divine Liturgy that he might know more consciously and more deeply the truth that his mother believed with simplicity.

Skete of St. Anna, Mount Athos (source)

The Need to Learn - Departure for Corinth

All this occurred up to the year 1934, when an unexpected and inexplicable event troubled his peaceful monastic life. Someone, whose name he never learned, sent him a copy of the periodical Anaplasis, which had a commentary on the position of the Professors of the School of Theology at the University of Athens regarding the Order of Masons. Their position was neither for nor against. But it sparked tremendous questions in the spirit of the young monk, who did not have the necessary education to judge for himself. There was no qualified person to help him with the agonizing question, nor could he find one. He was pondering over this issue day and night, wondering why the professors spoke the way they did. He wondered what Masonry is and what influence it had upon the Church. Since he could not find an answer, he thought of going "out into the world" - as the monks of the Holy Mountain say - in order to find appropriate people, to ask them, to have things explained to him.

Every monk, and the Hagiorite monks in particular, give very strict vows to live in the monastery of their repentance, their tonsure. They are not to abandon the monastery and their abbot, as a rule, does not give permission, with few exceptions, for a monk to leave.

Gerasimos the monk, who could no longer find peace, thought simply, monastically. He went to the icon of the Panagia to do his prostrations and to beseech her in prayer: He thought that if it is for his good to leave the Holy Mountain, upon requesting his permission, the Elder must give his blessing directly without hesitation. If he does not give his answer directly, or if he refuses, then this will mean that it is not the will of God to leave the Holy Mountain. This is what happened. The difficult Elder monk Chrysostomos Kartsonas, even though he had no other monk with him and he loved Gerasimos dearly, agreed to the request. But he agreed with the hope that his monk would soon return to him. The fact that he did not return soon created a sense of bitterness in the Elder Chrysostomos, who had the opportunity to see his monk again only after some thirty years, when Gerasimos was Bishop of Boston.

Theological Seminary - Corinth

In early Spring of 1934 he left the Garden of Panagia, the Holy Mountain, filled with hopes of finding answers to his questions. Immediately, his inner struggle was linked with his interest in attending the Theological Seminary of Corinth, about which his brother George, a teacher, had spoken to him. As a monk, he owned little and had economic difficulties - he could not afford to attend the seminary. These were overcome by his father who provided some funds and by Metropolitan Damaskenos of Corinth who provided him with a small scholarship (from the Monastery of Panagia of the Rock of Nemea, where he had to be enrolled as a member of the monastic community for ecclesiastical reasons). There he began a six year course of study at the Theological Seminary of Corinth. To receive his diploma from the Seminary he went to the Seminary of Arta toward the end of the academic year 1938, where the present Archbishop Seraphim of Athens and all Greece also completed his studies and with whom they had maintained a friendship.

It was a difficult and problematic situation for a young, but so mature, man to pursue studies surrounded by children ten or twelve years younger than he. This was the least of his problems. The diligence and the maturity of the young monk created serious problems for the professors. The monk sought a great deal; they offered a little. Often the tension in the classroom reached dimensions of significant proportions. It was only in music that the monk-student Gerasimos had no proficiency. His voice was weak and not very good.

He read a great deal and he listened carefully, but he completed his studies with even a greater spiritual thirst. In the meantime, in June of 1935, Metropolitan Damaskenos of Corinth, ordained him to the diaconate. A coincidence, a divine sign he was ordained on the Feast Day of the Holy Spirit, and he gave up his spirit on June 12, 1995, on the Feast of the Holy Spirit, just after Fr. Alkiviadis Calivas, in the presence of friends and relatives, offered the Sacrament of Holy Unction and read the Prayers for the Dying. Gerasimos offered sixty full years of service in the Priesthood.

Metropolitan Damaskenos of Corinth (and later Archbishop of Athens), who ordained Bishop Gerasimos to the Diaconate (source)

School of Theology - University of Athens

The element of unsatisfied spiritual thirst simply and naturally guided him to the idea of attending a Theological School. He wanted to study there also with the hope that he would be initiated more deeply into the truth, for whose sake he would enter into many deprivations. It is difficult for one to accept this, but positions and official authority never interested him. He did not even care to have his theological degree from the University, which he, of course, received. He was completely indifferent to such things. When someone understands the absolute nature of this indifference, he also understand how and why Bishop Gerasimos of Abydos remained a monk of the Holy Mountain, and particularly of the Skete of St. Anna, while he lived and served in the great metropolitan cities of the two continents and in the great university centers of the world: Boston, Oxford, Munich, Athens.

Given his advanced age, he prepared himself, nevertheless, for the introductory examinations to the School of Theology in Athens. He experienced some difficulties in the literary part of the examination, but had excellent results in the mathematical.

He entered the School of Theology and began with greater zeal to follow the courses which were being taught during that era by such great professors as Nikolaos Louvaris, Hamilcar Alivizatos, Vasilios Vellas, Panagiotis Bratsiotis, Demetrios Balanos, Georgios Soteriou, Gregorios Papamichael, Vasilios Stefanides, Panagiotis Trembelas and Ioannis Karmires. From the beginning, Professor Louvaris became his favorite, perhaps because of his profound thought and thorough knowledge of philosophy, which distinguished him, and which he used to emphasize the value of the truths of faith.

During this same period, other young men were studying theology and had distinguished careers later, such as Dionysios Psarianos (now Metropolitan of Kozani), Gabriel Kalokairinos (later Metropolitan of Thera), Makarios Kykkotis (later Archbishop of Cyprus), Silas Koskinas (later Metropolitan of New Jersey, U.S.A.), Basil Moustakis (author, poet) and Evangelos Theodorou (university professor of theology).

Unfortunately, just as the most substantive courses of theology were about to begin, World War II broke out in October 1940. In addition to all the other misfortunes, the students missed out on their regular studies. For the rest of his lifetime, Gerasimos of Abydos would regret this loss, which he considered great, particularly since what he was doing he was doing for a more comprehensive understanding of the truth. This is why he always valued greatly the service of teaching, the oral lesson, when the professor would attempt, through various ways, to analyze and expand the horizons of learning.

It is certainly not fortuitous that he himself loved to teach, and he loved it a great deal. While, as we said, he was indifferent to positions of authority, he had a great desire, from this time onward, to acquire the qualifications for teaching, to become a teacher, to speak all the more profoundly and convincingly about the simple and certain faith which he acquired experientially on the Holy Mountain.

In the meantime, and even though he did not have an exceptional voice, he was assigned to serve as a deacon at the Church of St. Dionysios the Areopagite, in the center of Athens.

Ordination to the Priesthood - The Orphanage in Vouliagmeni

The German occupation began and everything was overthrown. At the end of May 1941, with the breakdown of the front in the Greek-Bulgarian boundary, he was ordained - although he never considered himself worthy of it - a priest by Metropolitan Michael of Corinth. He now had the Priesthood for which he never considered himself worthy. However, he did everything that he could for an entire lifetime to honor it.

At this point we must emphasize that even when he became a bishop in 1962, he believed steadfastly that the priesthood is one. He believed that the bishop has nothing more than the priest, being only an archpriest, the first among priests. Primarily the bishop has the particular charisma from God to ordain other priests. The bishop as a hierarch is naturally the leader of the priests, who also celebrate the sacraments as validly as the bishop, once they have received the priesthood, the Sacred Tradition of the Church. It is understood of course that the priests must be united in faith with the bishop, who in turn also has the faith of the whole Church.

Once, when defending these opinions and explaining to me how and why he came these conclusions, he said: "How does the Eucharist which I celebrate as a bishop differ from the Eucharist which a priest of my diocese celebrates? Since there is no difference, we have the same priesthood."

At the beginning of the German occupation in 1942, Archbishop Damaskenos, who already knew and had helped him economically and morally and who continued to esteem him highly, appointed him to be Director of the Orphanage of Vouliagmeni. This responsibility offered nothing toward his profound theological aspirations. Those years, however, were so difficult that he felt obliged to accept the position. For three years, under terribly unfavorable conditions, he cared for the orphaned children not only to survive but also to experience some nurturing love.

During the course of the war and the occupation, he helped many people to survive hunger and persecutions, while, at the same time, he pursued with his familiar thirst the meager spiritual activities of the period: lecture, lessons, meetings and conversations with spiritual people. Liturgical life with the tradition of the Holy Mountain constituted the strong foundation, while he sought further knowledge that would help him understand those things he believed. During the occupation, he often visited his professor Nikolaos Louvaris. He continued to do this even after the professor had been imprisoned at the end of 1944, because of his participation in the last occupational government of Athens (at the request of Archbishop Damaskenos himself to serve as Minister of Education for national reasons. Among these reasons was the extraction of a promise from the Germans to expel the Bulgarians from the Greek territories in the north.)

Metropolitan Michael of Corinth (and later Archbishop of America), who ordained Fr. Gerasimos to the Priesthood, and appointed him as Chancellor of the Metropolis of Corinth (source)

Chancellor of the Metropolis of Corinth

Toward the end of 1945, Metropolitan Michael of Corinth offered him the position of Chancellor. With mixed feelings he accepted. He was concerned over this involvement in administrative matters, but being only thirty-five years old at the time he was daring enough to accept the post. He respected and highly esteemed his bishop Michael, who in turn loved and entrusted his Chancellor. Everything was going well, as long as he left most administrative matters in the hands of the secretaries of the Metropolis.

The ecclesiastical environment of Corinth included traditionalists, who were attached to the forms without understanding their essence, as well as certain hyper-nationalists and some liberals. He himself avoided all extremes, emphasized the need for understanding the essence of things, and worked diligently to establish a balanced view. In particular he wanted to be close to the priests, to create harmony among them, to support them, to point out to them that they should not be involved in the politico-ideological battles of the opponents in the Greek Civil War. Of course, he already held the opinion that Communism was an evil not only because it denied Christ, but also because it did not really care about man, and therefore could not help him essentially. But he never justified the crimes of the anti-Communists either.

During his years as Chancellor, when he was responsible for preaching and writing, he became more conscious of his limitations. This became clear to him in his capacity as the first co-worker of Metropolitan Michael in the publication of the periodical of that time The Apostle Paul, where he himself had to contribute articles and to publish, for the first time, some of his writings. It was then that he realized the demands and responsibilities of writing. He had become so sensitive to this awesome responsibility that, even though he wrote throughout his life and kept notes and expressed his opinions on paper, having composed entire commentaries on the books of the New Testament (on the Gospel of John, the Gospel of Mark, the Letters of St. Paul), including short articles on various theological and biblical subjects, only relatively few of them have been published: two complete volumes, a great many articles in periodicals and two additional texts - a book and a lengthy essay - are presently in the process of publication. The rest of his writings, gathered in five large cartons, still remain in manuscript form, not knowing yet what may be publishable.

Seeking Knowledge in Germany - The Study of Philosophy

His thirst for deeper research and knowledge was growing. His idea for studies outside of Greece was also maturing. From his professors, and particularly from Professor Louvaris, he had come to appreciate German scholarship. Ecclesiastical leaders were recommending England or America to him. He refused. He was offered the position of priest of the Orthodox Church in Munich. He accepted. In September of 1947 he was ready. He had strange and conflicting emotions. He had come to know the evil side of the Nazi soldiers while at the orphanage in Vouliagmeni, where he and all the orphans had been forcefully expelled. The condition of post-war occupied Germany was then terrible: poverty, crime and uncertainty. Nevertheless, the professors and the writers who had survived began once again to work diligently and systematically - so characteristic of these people.

Thus the Archimandrite Gerasimos, at the age of 37, embarked for Munich, Germany, without knowing any German. It was an adventurous trip. The occupation forces assigned him to a room and he began his work. It was the work of a pastor to a small trouble-filled congregation with many problems, and a systematic and extensive study of the German language. With patience and persistence he succeeded.

What did he study in the capital of Roman Catholic Bavaria? When he began he planned to study the New Testament. And this is what he would say when asked at the Roman Catholic School of Theology at the university. In fact, however, he had spent more time studying Greek philosophy. He considered it essential to learn how the philosophers thought about the great questions of man - especially about the question of God. He was fascinated beyond imagination by these questions, and he would be constantly testing whatever it was they were seeking, attempting, and devising. It was clear that inquisitive spirit was still unsatisfied.

All of these questions, immersed as he was in the Greek philosophers and especially Plato and Aristotle, inspired him and he appreciated them greatly. He appreciated this philosophical thinking so much so that he characterized an element of it as a propaedeia to Christianity. This is why his first book, the product of research of that period in Germany until the Spring of 1951, was given the title: Greek Philosophy as Propaideia to Christianity. This work was published in Athens in 1954.

Toward this direction in his thought, he was influenced by the famous Romano Guardini, who theologized while philosophizing and created literature while speaking. Literature appears to have never drawn the attention of Gerasimos of Abydos. However, to theologize by following the successes or failures of philosophy interested him a great deal. It was something like an exercise for him to comprehend more deeply the truths of faith, which philosophy did not possess. This approach and point of view has something that is wisely contradictory. But he insisted until the end of his life that philosophy actually helped him. And this despite the fact that all of his writings after 1954 do not show that he indeed was helped by philosophy. Everything clearly constitutes a deeper penetration into the revealed truth of Sacred Scripture and Tradition. How philosophy actually helped him is known only to him.

If we were to risk an interpretation of this fact, we would say the following: Gerasimos of Abydos, through his virtue of love and understanding for people, was able to appreciate any obscure or undeveloped formulations of the philosophers about God and man, in comparison to the truth, and as a spiritual man could show condescension for the failures of philosophers. Such failures, however, were for him occasions to marvel all the more the faith and the tradition which he had lived on the Holy Mountain. Moreover, he would always understand the historical journey of mankind, as well as divine economy itself, as a unified whole, in which he indirectly if not in expressis verbis included Greek philosophy. The intense and often successful - in minor issues - involvement of Greek philosophy with the great questions (something which had not yet been consciously and so deeply accomplished in world history) constituted a sort of preparation for man to come before the revelatory work of God and particularly that of the Incarnation. More concretely, he would emphasize throughout his life that we owe to philosophy our thirst for something higher, more sublime. It was philosophy that created in us the desire and brought us "thirsty" up to the point of the coming of Christ. And thirsty as we were, we "drank" from the living water of Christ and accepted Him.

Greece or America

The sojourn in Germany was coming to an end. It was Spring of 1951 when the first invitations - completely unexpected - reached him to consider going to America. Metropolitan Michael was now Archbishop of North and South America and he wanted to have his former Chancellor, Gerasimos Papadopoulos, by his side. But things did not go well at first.

He went first to Greece, where strong ecclesiastical personalities, such as Metropolitan Agathonikos of Kalavrita and Aigialeias, Metropolitan Prokopios of Corinth and others, wanted him to stay in Greece, promising to make him a metropolitan. While certainly not scornful of this latter prospect, he was not much moved by it. The then Archbishop Spyridon offered him the position of spiritual father at the large student dormitory of Apostolike Diakonia.

He accepted this responsibility, which lasted for only one academic year, but this proved to be a wonderful year for the students. In most such religious programs at this time, a spirit of moralism prevailed. Archimandrite Gerasimos Papadopoulos, however, was kindling in the souls of the students a love for Christ and opening their wings for flights into the life of the Spirit. He believed most steadfastly that the opening of the wings of the students had the greatest significance. He believed that with outstretched wings they could fly and find their way, even with some diversions they would reach their goal, they would mature, they would experience the true Christ. On the contrary, without wings at all, or with folded wings, they would never be able to fly; they would remain spiritually weak and immature infants throughout their lives. And if I have understood him correctly, it is in this that the deeper reason lies for encouraging the students then to study and pay attention to the teaching of Louvaris. While disagreeing with him on many points, he nevertheless appreciated how his writings helped the students to spread their intellectual wings. He broadened, rather than narrowed, the ways of the Spirit. He appreciated his work as the spiritual father of the students and had determined to stay in Greece.

Holy Cross Orthodox Seminary, Brookline, MA (source)

America - Holy Cross School of Theology

Once again America beckoned. Archbishop Michael had not been disappointed. He sent a bishop to convince Gerasimos to come to America. He relented and accepted the invitation. Various communities were considered for him in some of the larger American cities. Fortunately these proposals were not successful and Archbishop Michael appointed him to be Professor of New Testament and chaplain at Holy Cross School of Theology in Boston, near some of the greatest universities of America.

By July of 1952 he was in Boston. He had to prepare himself systematically. He worked most diligently in a super-human manner, doing research and preparing texts for the students to study. They in turn were not always well equipped and the work of teaching them was very difficult. He had no time, after all, for extensive scholastic literary, historical and critical analyses. He had to concentrate on the necessary, the basic, the essential elements. This was in harmony with his own character. He therefore drew and concentrated the interest of the students upon the presuppositions, the goal, the thought, the theology of the New Testament writings. The end result of this effort was the ease and depth of movement within the whole realm of the New Testament.

Many of the proposals of the liberal interpreters of Protestantism he considered to be immature things. Once when they told him that Bultmann supported that the original order of the chapters in the Gospel of St. John was different, he responded like this: "We cannot prove that the order was originally different. Bultmann supports another order of the chapters simply because with that order he understands John better and thus would have preferred the Gospel to have been written in that order." Such forms of criticism and the questions raised about Sacred Scripture by many liberal scholars tend to deny something in Scripture, rather than to help man to understand more deeply the truth.

In the area of criticism he did not negate everything. For example, he agreed that a particular saying of the Lord could have been uttered originally in a somewhat different form. He believed, however, that for the Evangelist to record it, it was certainly uttered by the Lord and it constituted an essential aspect of the faith and the Tradition of the Church. It is a revelation. He attempted to comprehend revelation for himself and to make it understandable for the students by also using reason, to a certain degree. He held that Christian Faith possesses an inner logic and consequence which must be comprehensible. It was not an easy matter, yet he pushed on in that direction as much as he could, as much as it was permitted, after all, by the truth that is inexhaustible for us. As soon as he would reach the ends of logic or of his own capabilities, he would surrender himself completely to the declaration of Scripture, to its straight forward theology, to the "so it is written." Any fantastic creation of new truths, that is, of another Christ, or a denial and a falsification of what we have in Scripture constitute a heresy. He only sought to go deeper into the divine truths, to attempt to know more profoundly the truths of Scripture. This is what he considered to be the goal of the exegete and of the theologian.

He believed, however, that the exegetes and the theologians have difficulties in understanding the truth, primarily because we do not live as much as we should the life of Christ. If we surrender to Christ, then the Holy Spirit "will guide you (us) into all the truth" (Jn. 16.13-15).

Father "G.U.L.F."

His life at the Holy Cross School of Theology was not without difficulties. The spirit that motivated him was different from the spirit of the Dean, Fr. Ezekiel Tsoukalas, who had the unfortunate inspiration to name him sub-dean of the School. The conflicts were many. Archimandrite Professor Gerasimos refused to oppress the students through the school program. He confronted them with a different spirit. He would convince them to work, but freely, uncoerced. And the students would respond accordingly. They came to more than love Gerasimos, who quickly came to be known in the code language of the students as Fr. "G.U.L.F." - the initial letters for Gerasimos, Understanding, Love, Faith. These were the perennial issues he discussed with them, and that's why they had become his code name for many years.

With every opportunity and particularly at night his room would fill with students. There were never enough chairs and they would sit on the floor and in the hall. They made inquiries, carried on discussions, listened and were satisfied with much love and learning. It was what these young men were seeking, particularly in this situation, who would in two or three years be ordained into the priesthood.

He lived for the students, no more no less. He worked to acquire knowledge and he prayed for God to give him perseverance. Thus he overcame the crises and the disappointments coming from the Dean, who reached the point of first depriving him of his position as Sub-dean and then asking for his removal from the School. The Dean did not succeed in his latter plan, much to the delight of the students, who lost no opportunity to express their esteem and devotion for their professor, "Fr. G.U.L.F." This reaction served as the highest form of consolation for the professor, who found perseverance and persistence to continue the work of teaching and nurturing spiritually the students to the best of his ability.

During his tenure at Holy Cross it was necessary to teach courses beyond his own field and to undertake even the entire administration of the School, as Acting Dean, which he did not particularly like.

Service to the Orthodox of America

His popularity, which was simultaneously scientific and spiritual, passed beyond the boundaries of Holy Cross. Very soon he was invited and in demand for lectures, homilies, and director of retreat discussions in various cities of the United States.

He gave particular attention himself to the New England Federation of Orthodox Students. It was the first environment, outside of the School, where he had been invited to confront certain critical issues - theological and social - but in a different manner than the one he had been exposed to at the University of Athens and later of Munich. Here the interests of the students, who came from various university schools, were of a more general character and were not contained strictly within the realm of theological subjects. The need to respond to such demands required him to be initiated into and to become conscious of the intense concerns of the people of the new world.

These critical issues had their own presuppositions and, in their external signs, were very different from those Fr. Gerasimos knew in Greece and in Germany. Therefore, the speaker had to acquire as soon as possible a new inner private training, if he really desired to help these young people and if he indeed possessed the necessary capabilities. And he succeeded. This is why he was greatly esteemed in these circles, where he became a close friend of the well-known Russian theologian, Fr. Georges Florovsky, who also gave lectures in these same circles. This was only the beginning of his activity outside of Holy Cross. He extended himself to ever broader areas and to other metropolitan areas besides Boston. This activity often took the form of a series of lectures during spiritual retreats or of a series of Bible studies.

This activity continued until the last winter of his life. He also pursued advanced studies at universities in Boston, receiving a Master of Theology in 1957 from Boston University. This grounded him and prepared him for the spiritual reality of the New World. This was his fourth and final stage of studies, which he continued with youthful zeal until his last breath. Of the three previous stages of studies, the first was accomplished on the Holy Mountain, the second at the University of Athens, and the third at the University of Munich. One must appreciate the presuppositions, the character, the depth and the breadth of each of these stages, if one truly wants to understand their assimilating spirit and their benevolent influence upon Gerasimos, the Bishop of Abydos.

The Reality of Orthodoxy in America

How quickly he came to understand the problems of the new world is obvious also in the fact that only several months after his arrival in America, he dealt with courageous realism the great problem of Greek Orthodoxy in America, the problem of the Greek language. He not only spoke about it, but he also wrote about it, and declared openly that if we want to teach Orthodoxy to our children, if we want them to want to come to our Church, and especially if we want them to be consciously Orthodox Christians, we must speak to them in English, but without this to mean that we should abandon the Greek language. He took this position in 1952 and 1953, when no one would dare approach this dramatic problem among the great multitudes of diaspora in America. He favored the introduction of some English in the Liturgy from that time, yet he still insisted until his end that no matter how many decades pass, no matter how many changes take place, no matter how little the congregation understands the Greek language, a portion of the Divine Liturgy, even a small portion, must continue to be in Greek, in the language of Scripture and our ancient Tradition. The teaching ministry of our Church, however, must be in the language of the people.

In order to more fully understand this, we must emphasize something else. In the innermost being of the Archimandrite Gerasimos of that period a real drama was unfolding. He, who had a real passion for the Greek philosophers and so loved their thought, was also and first of all a monk of the Holy Mountain. He experienced Orthodoxy upon its acropolis; he experienced it in the hearts of the ascetics, who lived consciously the Sacred Tradition of nineteen centuries of Orthodoxy. This is how Orthodoxy was planted into his deepest being. Orthodoxy led to salvation. Yet, Hellenism had also profoundly influenced his spirit. Fr. Gerasimos felt the obligation to give preference to one of the two. A violent inner struggle took place. He struggled to see if he could have both fully. It was impossible. He was disappointed and frustrated. The decision had to be made. The soul nurtured by the Holy Mountain took precedence. Salvation must come first, the Greek language can follow. Christian Orthodoxy is first, Hellenism follows.

Hierarch by Obedience

At the end of 1961 Archbishop Iakovos insisted that Fr. Gerasimos become bishop for Detroit. Archimandrite Gerasimos refused for two reasons. He loved his teaching ministry at the School of Theology very much, which he considered to be suited for him and which he would have to abandon. Secondly, he felt that he had no calling for administrative work, which he would be obliged to carry out as bishop.

The Archbishop, however, who esteemed him very much, both for his capabilities and for his spiritual life, did not give up on the idea. Months later, without telling Fr. Gerasimos anything, the Archbishop spoke to Patriarch Athenagoras. On April 6, 1962 the Synod of the Patriarchate elected Gerasimos as titular Bishop of Abydos. On the day after the election the Archbishop announced the news to Gerasimos, who chose not to say no to the voice of the Church. On May 20, 1962 he was consecrated in Boston and would serve as the Bishop of the Diocese of Boston.

Patriarch Athenagoras, under whose leadership, the Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate elected Fr. Gerasimos a bishop (source)

Life as a Bishop

His period of service in the Diocese of Boston would not continue for too many years. Certain difficulties in the Pittsburgh Diocese required the presence of Gerasimos of Abydos. As he began his ministry as a bishop, which continued administratively until 1977, he was fully aware of his own shortcomings, those of his flock and, naturally, those of his priests. He never liked absolute formulations, because they did not belong to the tradition, nor were they realistic. And in order to face the problems of the flock in an edifying manner, he followed a traditional principle: economia and flexibility on secondary matters, strictness on matters of faith.

This principle he attempted to inspire into his priests, with whom he labored as co-workers. He had regular assemblies with them and - most importantly - he know how to listen to them, a prized virtue in a bishop. Thus he managed to be supportive in their difficult work as priests in the communities, to earn their trust and to make easier the solution of many problems. He did not have the slightest difficulty in saying to his priests that they, in their parishes, are the "bishops." Naturally there were certain disagreements and conflicts. He was the bishop and had tremendous responsibilities, the primary responsibility, and often had to impose the opinion which he judged to be the correct one. But even this was always done with consultations, with discussion of the issues, so that it was not like some authoritative and autocratic imposition.

His episcopal ministry both in Boston and in Pittsburgh was truly successful, since undoubtedly the flock and the priests considered him as their spiritual father, who wanted and could help them spiritually.

He worked and behaved in such a way that all wanted to approach him and to confide in him. All knew that he had many things to offer on all the matters of the faith and the spiritual life. Yet, he never believed that his service was perfect, or that he had avoided mistakes. He considered his episcopal ministry to be a soft-spoken one. He did not try to impose his authority or impress people. He did not change or overthrow any existing conditions. He only wanted to help the people live more fully and more deeply their life in Christ, the life of the Church. In particular, he always tried to show the faithful the wonderful and saving majesty of the Divine Liturgy.

During the synods of the Greek Orthodox Bishops of all America, under the presidency of Archbishop Iakovos, his presence was positive and edifying when he spoke and even when he did not speak. He had the prudence to listen with an open mind and to understand that, in general, the opinion of the Archbishop would prevail. But he also had the necessary courage and outspokenness to express his own opinion and to support what he believed to be correct, independently of any concerns that might be unpleasant. In such circumstance he never fostered ulterior motives nor a disposition to insult anyone.

In all of his activities and various cooperative efforts with simple lay people, with officials, with priests, with fellow bishops and with the Archbishop he always sought to achieve a balance - a moderation in all things - which he managed to transform into what he himself would call reality. This realism presupposes the knowledge of what is ideally correct, the recognition of the limited capabilities and dispositions of people, as well as the pursuit of what is attainable. One who is spiritually advanced is never satisfied with merely what is simply attainable, but one accepts it with condescension, hoping that at least it will serve as a first step for further progress.

Interlude at Oxford and Return to Holy Cross

In 1965, as Bishop of Boston, after continuous teaching and pastoral labors, he felt something like an inner emptiness. At the same time, he was seeking out great scholars to discuss certain important problems of theology in the New Testament. Moreover, he was seeking a brief period of relaxation, to set aside his pastoral responsibilities for the sake of relaxed theological discussions without interruptions.

Thus, for several months he went to Oxford, England. He visited libraries and attended various lectures. But this was secondary. The significant thing for Bishop Gerasimos, who by now had 55 years upon his shoulders, was the opportunity to discuss at length with many - over ten - prominent professors and exegetes. He was prepared to listen, but was impressed because most of them were also prepared to listen to him. They were not Orthodox, but he was nevertheless interested in seeing how they thought about critical issues, about issues that perhaps they did not care to write about. Within his soul the Orthodoxy of the Holy Mountain prevailed absolutely, but he was prepared to accept some corrections in his thought about the person of Christ and the divine Economy. Most characteristic of his character and the degree of his spiritual life was his great love for discussions, concerning the person of Christ and the difficult theological issues related to the life of faith of the faithful. He did want to discuss other subjects, and had no interest in hearing what one is doing, how another was insulted, and other similar things. Until his very last days and hours, he wanted to discuss with passion only theological subjects, about "our Christ," as he used to say. It is characteristic that in April 1995, after several months, professor and Metropolitan Demetrios of Vresthena, a person he esteemed highly, came to visit him. After the usual greetings about their health, the two bishops sat down because Bishop Gerasimos wanted to discuss and to ask questions. To the Metropolitan's inquiry, "What shall we talk about, Geronta?" Bishop Gerasimos responded: "Why, about our Christ, of course, what else?"

Ultimately, Bishop Gerasimos was not enlightened in Oxford, as he would say, from the discussions which he enjoyed with the truly wise persons he had met there. He appreciated them, he relaxed and continued there, until certain problems at Holy Cross forced the Archbishop to recall him to Boston in a hurry. It was then that he was given the responsibility to be the Dean of the School of Theology, which he, of course, loved most dearly. Later, of course, other problems in Pittsburgh would require his peacemaking presence there.

Retirement

At the age of 67, that is, in 1977, he retired from the administrative and pastoral responsibilities of the Diocese of Pittsburgh. He had asked to retire in 1976. He wanted to find time for writing and for spiritual cultivation. He always considered very little that which he had achieved internally. Finally, his retirement was accepted on June 19, 1977. What impressive coincidences! He was ordained a deacon on June 17, 1935, the day of the Holy Spirit; he gave his spirit on June 12, 1995 on the day of the Holy Spirit.

The news of his retirement, for those who did not know him well, made an impression. He was still at the prime of his life, working many hours in the day, and people did not expect that he would retire. As a clergyman, a teacher par excellence, a writer, a reader and a spiritual father, this act of his was also perfectly understandable. And this is why for them the Bishop's retirement was a courageous act. This is why it was esteemed and marveled at from all sides.

Moreover, everyone knew that Bishop Gerasimos was not seeking honors and authoritative positions, thrones and acclamations. But precisely because he did not seek thrones or authorities, he was truly enthroned in the hearts of the people. And he remained enthroned there, where he still is and will always be. In Pittsburgh, a farewell banquet was organized in his honor, and the greetings and farewell wishes expressed that evening constitute a monument of gratitude and profound estimation for the departing bishop. Representatives of the clergy and of the communities, of the national Greek-American Associations, and of the faithful people of the Diocese spoke most affectionately and with great admiration for their beloved bishop. Naturally, of course, the Archbishop also spoke to honor Bishop Gerasimos.

Before, during and after the farewell banquet, Bishop Gerasimos felt various conflicting emotions: What had been completed in his life? Should it have come to an end? What was to begin now? Had forty-two years of intensive preparation and activity as a clergyman received their seal of completion, or would they find some worthy continuity? And what form will such continuity take? He had thought about everything a year before. Now, however, he was pressured emotionally by these thoughts. And the pressure was considerable. Most of all he was sad over his separation from the people he loved and who loved him. His consolation was that a new bishop, younger in years, would be able to offer more for them and would love them just as much. He believed that people ought not to grow too old in these positions.

Immediately after his retirement, he traveled to Greece. He went back to the Holy Mountain. His cell at St. Anna was now in ruins. A thought he had about living there the rest of his life took flight when he looked upon his ruined cell and the little chapel, where he lived and prayed for four years in simplicity, with frugality - a characteristic virtue and mark of his entire life.

At this point I shall describe an incident, over which I had a considerable internal debate regarding whether or not to record it. Because, however, it has been confirmed by an abbot of a monastery, I feel that I should mention it. The visit of Bishop Gerasimos to the Holy Mountain coincided with the feast day of the main church of the St. Anna Skete. As a bishop of the Ecumenical Patriarchate and a former monk of Mt. Athos, a few of the old monks who remembered him, particularly the monks of Fr. Chrysostomos Kartsonas, naturally, wanted him to celebrate the Divine Liturgy at the great festival of St. Anna. Bishop Gerasimos, however, because he had been living in America had a short, trimmed beard. This prompted some of the monks of the Skete to oppose his liturgizing because, they claimed, the people would be scandalized seeing him with a trimmed beard. When they clearly intimated their perplexity over this matter, Bishop Gerasimos dismissed it, giving it no thought at all. He simply went and stood in a back corner of the church as if nothing had happened, and he remained there from the beginning of the all night vigil until late the next day when the Divine Liturgy was celebrated. There, alone, without any distinctive signs, a stranger among strangers, he recalled his old monastic experiences and prayed as much as he could. It is the custom during the vigil of the feast day of St. Anna for the hesychast ascetics and hermit monks, who live a very austere monasticism in poor, isolated kalyves, far from the Sketes and Monasteries, to gather silently in the central church. After the liturgy, one of these ascetic monks approached two leading monks of the Skete and asked them: "Who was that clergyman who stood in that corner stasidi?" They explained to him that he was Bishop Gerasimos of Abydos, who had not been permitted to liturgize because he had trimmed his beard. Then the ascetic monk crossed himself and told them: "What have you done? How could you? All night long I could see over his head a light like a dove, while over your heads there appeared something like little devils!"

I verified the information regarding this incident, and when I mentioned it to Bishop Gerasimos himself, he confirmed everything except the reference to a dove, about which he knew nothing.

At first, after retirement, his thought was to settle somewhere in Greece. Arrangements had been made with me because we would have been staying together. He even had sent ahead a small portion of his books, since his destination was Greece. Deliberations had also been made for him to teach a few hours at the Rizarios Ecclesiastical School in Athens.

Picture of a vigil service at the main church of the Skete of St. Anna (source)

America Asks for a Spiritual Father

While there were many signs indicating that Bishop Gerasimos would prefer to settle in Greece, and particularly in Athens, to be near the libraries, the clear and fervent voice of the Greek Orthodox faithful of America moved him and won him over. Messages would come to him in Greece, informing him that he was wanted and needed there in America. I remember how the now Metropolitan Silas (Koskinas) had come then to conjure me: "Do not pressure your uncle to remain in Athens, we need him in America! We need a spiritual father to talk to, our priests especially and even we the bishops."

I too had been shaken by all these urgent messages. But I had not yet understood how much the blessed Elder loved the Theological School of the Holy Cross. He submitted to the invitations of the people of America, but with the understanding that he would return to his beloved School, to teach according to his ability, living on campus but not being involved with the administrative responsibilities of the School, of the Diocese, or any other institution.

Again at Holy Cross - Teacher, Writer, Counsellor

His terms were accepted. They sent him an urgent express letter. He obeyed the voice of the Church. He returned and took up residence in a typical student apartment, consisting of two small rooms. This happened on November 1977.

There at the School, in a truly idyllic environment, on that verdant hill with innumerable trees, many of which he had planted himself and cared for dearly, Bishop Gerasimos lived another eighteen years as professor and counselor and spiritual father to the students. It was for this purpose that he had been invited to come back. In fact, the blessed Elder felt that he had never really left the School, but rather had lived there continuously since 1952, when he first came to America. Of course, he had served ten years as Bishop in Pittsburgh, but because he was always close to the School in spirit, he felt that he had never been absent from his beloved School on the hill.

At the School, without seeking it, he became immediately the spiritual center.

For four years he continued to teach with the load of a full time professor. Later he taught part time and then occasionally. For a few years it was necessary to teach the course in Dogmatics. He used to read and prepare himself with youthful vigor. He took advantage of this need of the School to study more profoundly for himself the Fathers of the Church, and to attempt to transmit their spirit to the students who would become priests in the future and would need to live with the help of the Fathers.

Study and Writing to the Very End

It seems incredible, but in his retirement Bishop Gerasimos would work all day long. Until the very last days and hours of his life, he continued to read and to write, in spite of the fact that since the beginning of the 1980's serious health problems had appeared. A very serious case of septicemia had kept him for days in a state of aphasia. Later, problems appeared with his heart, which were treated with pills and patience. But the rhythm of his work was not interrupted. Even in the summer, during his vacation, he followed the same routine without losing any time. During virtually all of the summers after 1977, he traveled to Greece. And, of course, Greece meant primarily the village where he was born, Bouzi (now called Kyllini) of Corinth, Stymphalia, on the sides of Mt. Tzereia. He would spent about a week in Athens at the most and then he would go directly to Bouzi. There, again, during July and August, he would rise early and after his morning prayer, would begin his study immediately. He did the same in the afternoon until late.

Whenever he arrived from America, he would seek out significant publications in contemporary Greek Orthodox theology, and particularly works of the Church Fathers commenting on biblical passages. He would not only read these books but would also take notes from them, marking in pencil important passages and whatever he considered useful to him. He had read and taken notes from virtually all of the significant works of the biblical scholars in the Schools of Theology of Greece. Parallel with this study, in spite of old age and the health problems of his heart and his feet, he did not neglect to serve the Liturgy in the various larger or smaller mountain towns. He never refused an invitation. He usually only refused to wear the episcopal miter during Liturgy. And so each summer the faithful in the mountain towns of Corinth looked forward with great anticipation for a visit from Bishop Gerasimos.

During his years in retirement, Bishop Gerasimos devoted much time to teaching, but also to preparation of his very significant book, Orthodoxy, Faith and Life and a Greek edition in one volume, Orthodoxia - Piste kai Zoe, in Athens in 1987. This is not the place to analyze this work, but it should be noted that it sums up a very profound analysis and understanding of the work of divine economy for the salvation of the world. This particular analysis of the work of Christ surpasses in depth but also in simplicity many other parallel attempts. In this book an Orthodox bishop speaks about Christ and the Church, a bishop who for many years was a persistent researcher, who studied considerably the secular wisdom, who knew well the opinions of the heterodox, and - most importantly - he had been living the truth for fifty years in prayer and worship. Thus, the work presupposes knowledge and personal experiences and is written in order to edify the reader in a spiritual way. Whoever studies this book, regardless if one is a theologian or not, he will be filled with divine spirit and will be virtually incorporated into the Church.

Following this book, Reflections on Our Christian Faith and Life was published in 1995, after Bishop Gerasimos fell asleep in the Lord. Another work on the eschatological faith of the Church will be printed in the very near future.

The teaching and the writing work of Bishop Gerasimos drew, of course, the attention, the estimation and the admiration of professors, students and ecclesiastical circles. Moreover, during these eighteen years, the requests for lectures and Bible studies in various communities and university centers throughout the United States continued to come one after the other. Consequently, an ever widening circle of spiritual men and women and scholars were able to experience and appreciate the gift of the blessed Bishop Gerasimos.

The Abba of America - Living the Sacred Tradition

But above and beyond all these things that have been related, the blessed Bishop Gerasimos was also something else: he was an Abba - a Father. He was a teacher to whom the young and the old would run at every difficulty with strictly theological issues. He was also the spiritual Father, the Abba, the comforter, the counselor. A whole world lived in the School and even a greater one far from it. But everyone knew that up there on the hill, a little beyond the chapel of the Holy Cross, there lived a wise and holy Elder. In his simple quarters he prayed and studied alone and was always ready to receive all. The very certainty that there lived such a man was itself a consolation. The students would pass by his window and would feel secure. From the central buildings and the classrooms the professors and administrators knew that at any difficult time the wise Elder had something prudent and helpful to say to them. The pain and the crossroads of life, the falls and the sins of spiritual people would take the path toward the room of the wise and holy Elder. Innumerable people, clergymen and laymen and laywomen, placed before him, again and again, the failures they experienced in their upward spiritual journey. He in turn would share their pain, but would also share their joy wherever they had succeeded well. With or without the stole over his neck, the blessed Bishop always served as an Abba, as a spiritual Father, as a Father confessor and comforter. And everyone - indeed everyone - would leave his cell always, more or less, strengthened and renewed in spirit.

This work of the Elder, the Abba, was among the most burdensome and most difficult in the life of the Church. It staggers and empties the spiritual man who has profound sacred experiences and who possesses spiritual wealth that he readily offers to those who come to him. (People simply did not come to him who did not possess such a spiritual life). The blessed Bishop possessed such a spiritual life. He had it in abundance indeed, but he himself believed that it was poor, very poor.

This is why until the very last hours of his life he continued to renew himself, to live with prayer and worship the truth, the mystery of Christ and of life, as he loved to remark. This was so because Bishop Gerasimos, although surrounded by the greatest universities of the world, lived with the daily prayer services as a simple monk. These nurtured him; through them he was "rebaptized" and lived. Early in the morning and every evening he was present, as in the old days on Mt. Athos, in the Chapel of the Holy Cross. And he loved to be the celebrant of the Divine Liturgy, as a simple priest, even more frequently than the young clergymen who loved to serve.

It was enough for the students to see him in the Chapel without fail as an old man of so many years to be silently but consciously instructed, nurtured and edified. With or without saying it, they felt certain of the fact: the Tradition lives! Bishop Gerasimos was the Tradition! No one could tell them that the Tradition had been lost, that it was only in the past. They had the Tradition alive before them! This is the great contribution of the blessed Bishop. This is perhaps the reason why he had to live the faith and to continue his ascetic struggle in America, in "our Theological School," as he loved to say.

Taken from the book: Agape and Diakonia: Essays in Memory of Bishop Gerasimos of Abydos

Through the prayers of our Holy Fathers, Lord Jesus Christ our God, have mercy on us and save us! Amen!

No comments:

Post a Comment